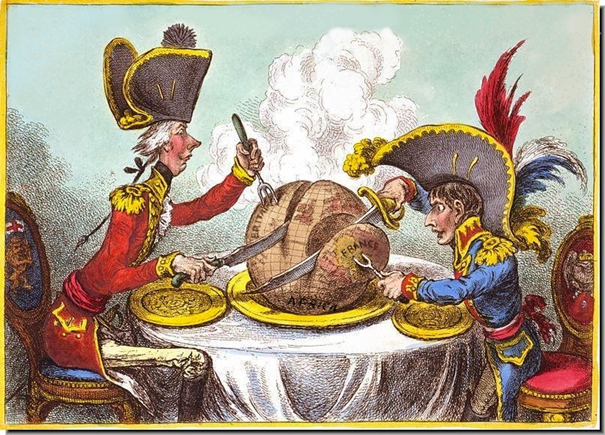

Highlight 10/2022 – The Two ghosts in the house: The legacy of the British and French colonialism which haunts Africa

Mireille Pakisa Nzuzi, 3 March 2022

Image source: World History, Culture, and …- Mapa Mental (mindomo.com)

From time immemorial, one comes to the acknowledgement that the legacy of colonialism is long and bloody. De-colonialism gingerly saw the people of Africa achieve independence. The dichotomous legacy of the latter continues to haunt Africa’s march into its future.

Acknowledgedly, a preponderance of Western European nation-states took part in the “Scramble for Africa”. The two heavy weights with the longest enduring legacy on the African continent are still Great-Britain and France. It is these two nation-states that extolled colonial policy in Africa and their work in shaping African governments, which can potentially, and one should trade with great prudence to, forgo alluding to this as a monocausal factor, explain the troubled legacy that continues to plague many African countries. Great Britain and France, each in their own rights, sought the implementation of a political lexicon that mirrored the hallmark of the heartland.

On one hand, the British approach to rule in Africa, concocted and vanguard by Lord Frederick Luggard, came to be portrayed as favoring a more “in-direct rule strategy”. Governing the colonies from far afield through native instrumentalities, bequeathing respect for traditional culture, religion and power structures. One might ask indeed, was the propensity of using this approach out of pure necessity? Would London have been able to galvanize enough economic resources and manpower to foresaw the entirety of its colonial landscapes from the center? This ought to be maybe why they sought to endow the local kings, chiefdoms and aldermen with greater responsibilities which includes but not limited to maintaining law and order, enforcing colonial decrees and books/records keeping[1]. Hence, enabling the colonized societies to adjust slowly but surely to the imperial presence and therefore, helped to reduce the tensions ensuing from change and acculturation.

On the other hand, the France interaction with its colonies was (as it remains today) one depicted by a push assimilation to the “French way”[2] while also promoting centricity of its sovereignty. A “direct rule strategy”, featuring a control from Paris in the day-to-day operations of its colonies. The colonies were to be considered as an integral part of France. Laws governing the latter directly ensuing from Paris. Colonies were allowed to send representatives to the French national assembly. While the Senegalese, Léopold Sédar Senghor, was permitted to partake in the drafting of the French constitution[3]. The Ghanaian, Kwame Nkrumah, could have only wished.

Compared to the abovementioned British administrative system, in the French colonies, key positions were held by French personnel[4] in provenance from the metropolitan heartland. On education, a system founded on dissimilarity amongst colonies and permissibility of teaching in indigenous African languages was the British’s way[5]. Whereby, the French enshrined homogeneity, centralization and “la langue de Molière” not only ought to be the norm but spoken correctly.

Economically, the English-speaking dependencies were encouraged to live within their means, and apply to Westminster for support only in terms of special projects on an ad hoc basis. Such a level of self-governance was unheard of in the French colonies. Many of them were highly dependent on subsidies from France[6]. Thus far, all Sub-Saharan African countries colonized by France except Guinea, still share the CFA franc which has been until May 20th 2020 partly managed by the Bank of France. However, France has not withdrawn fully from the managing stakeholders of the currency as it’s still the guarantor of the CFA zone. On Trade, France had, and still exercises great influence when it comes to the choice of trading and investment partners of its former colonies. Such luxurious silver spoon has come to miss Britain’s mouth.

Additionally, a sharp contrast could be noted in the mere fact that France due to some agreements and/ or accords can still intervene militarily in many of its erstwhile colonies[7]. Hovering through The Washington Post as of late February 2022, one will easily stumble on France withdrawing troops from Mali[8]. Such military intervention in the former colonies, will revert to be unthinkable for Great Britain.

Speaking in vastly general terms and the degree of centralization or lack thereof, the two approaches differ markedly. As a result, former British Colonies such as Ghana and Nigeria enjoy much higher degree of economic prosperity, stable government institutions and greater social trust than in the erstwhile French controlled Mali, Chad and/ or Central African Republic.

Indeed, it may be true that the more hands-off approach by the British led to more stable institutions by laying the foundation allowing self-governance. Hence, when the untombed angel of independence came knocking, a sink of these indigenous kings, chiefs and aldermen had become accustomed with the fine art of ‘modern’ governance. Nonetheless, it is still in ones moral rectitude to note that both types of rulings were precursor and conduit of an unjust system of economic exploitation. The ghosts of colonialism will continue to haunt Africa for some time, withholding at once from the proclivity of making European colonialism the scapegoat, how African states can come to terms with and adapt from these experiences will be what determines their bearing for the future.

Mireille Pakisa Nzuzi, Highlight 10/2022 – The Two ghosts in the house: The legacy of the British and French colonialism which haunts Africa, 3 March 2022, available at www.meig.ch

The views expressed in the MEIG Highlights are personal to the author and neither reflect the positions of the MEIG Programme nor those of the University of Geneva.

[1] Ali A Mazrui, ‘Francophone Nations and English-Speaking States: Imperial Ethnicity and African Political Formations’< Power, Politics, and the African Condition > accessed on 21 February 2022.

[2] Laura Fenwick, ‘British and French Styles of Influence in Colonial and Independent Africa: A Comparative Study of Kenya and Senegal’< https://auislandora.wrlc.org/islandora/object/0809capstones%3A10/datastream/PDF/view > accessed on 21 February 2022.

[3] Ambe J Njoh, ‘The impact of colonial heritage on the Development in Sub-Sharan Africa’< https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1023/A:1007074516048.pdf>accessed on 24 February 2022.

[4] Derwent Whittlesey, ‘British and French Colonial Technique in West Africa’< https://www.jstor.org/stable/20028773?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents > accessed on 24 February 2022.

[5] Ali A Mazrui, ‘Francophone Nations and English-Speaking States: Imperial Ethnicity and African Political Formations’< Power, Politics, and the African Condition > accessed on 21 February 2022

[6] Ambe J Njoh, ‘The impact of colonial heritage on the Development in Sub-Sharan Africa’< https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1023/A:1007074516048.pdf >accessed on 24 February 2022.

[7] Ali A Mazrui, ‘Francophone Nations and English-Speaking States: Imperial Ethnicity and African Political Formations’< Power, Politics, and the African Condition > accessed on 21 February 2022.

[8] Danielle Paquette, ‘France announces withdrawal of troops from Mali, reshaping the fight against m extremists in West Africa’< https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/02/17/mali-france-troops-withdrawal-macron/ > accessed on 25 February 2022.