Highlight 49/2025: Europe’s New Trade-Off: Can Security Reinforcement Coexist with the Social Model?

Kevin Villacis, 15 December 2025

For decades, European debates on public finance have been shaped by a simple intuition: every euro spent on defence is a euro taken away from social protection. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 and military budgets began to rise across the continent, this idea quickly resurfaced. Europe, many warned, would be forced to choose between security and welfare.

This highlight uses recent fiscal data at the national level to challenge that claim. The evidence suggests that the supposed trade-off between defence and social spending is largely misleading. Europe’s response to the security shock did not automatically dismantle the welfare state. Instead, it unfolded within existing fiscal and institutional structures, producing markedly different outcomes across countries.

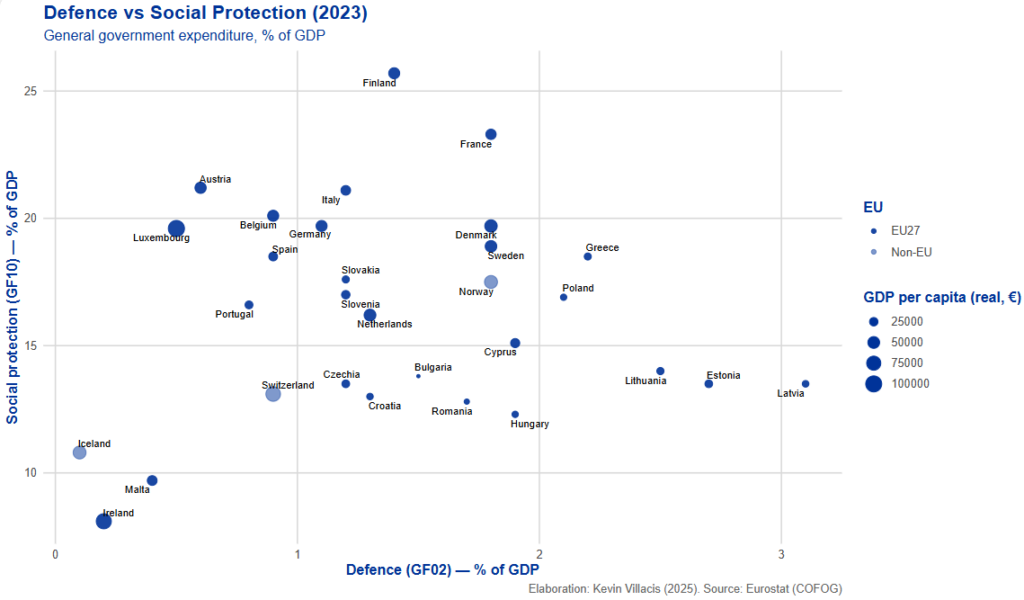

Figure 1 plots defence spending against social protection expenditure across European countries in 2023 (most recent available data in the European Statistical Office as of December 2025). If military outlays mechanically crowded out welfare, a clear negative relationship would emerge. It does not. Countries with some of the most generous welfare systems in Europe, including France, Finland, and Denmark, also display moderate to high levels of defence spending. The anticipated zero-sum relationship between welfare and pensions is not visible, at least at the aggregate level.

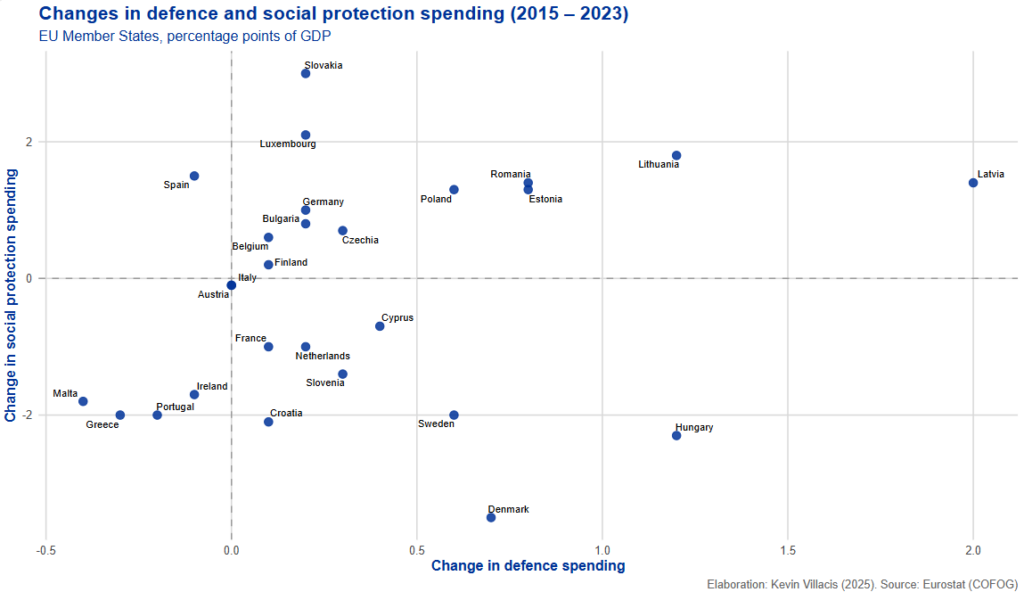

Levels alone, however, can be misleading. Figure 2 therefore examines how countries adjusted between 2015 and 2023, a period that spans both the post-Donbas security environment and the invasion of Ukraine. Here, a more nuanced picture emerges. Several countries increased defence spending while social protection stagnated or declined slightly, including parts of Central and Eastern Europe and some large Western economies. At the same time, countries such as Germany, Poland, and Lithuania managed to raise defence expenditure without cutting social spending. Thus, trade-offs do exist, but they are selective rather than universal.

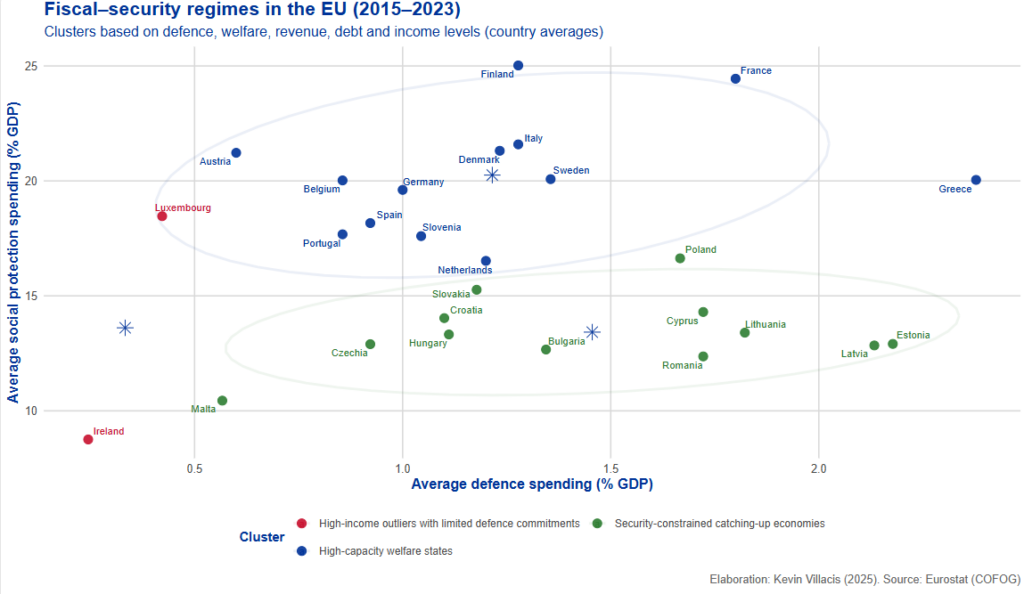

These divergent trajectories suggest that defence and welfare outcomes cannot be understood by looking at countries in isolation. Instead, they reflect deeper structural conditions. To capture these, the analysis groups European countries into fiscal security regimes based on defence effort, welfare generosity, revenue capacity, Maastricht debt levels, and income per capita. This approach shifts the focus from short-term political choices to the fiscal environments within which governments responded to the security shock.

Figure 3 presents these regimes by plotting average defence and social spending over the period 2015–2023. Three distinct configurations emerge. High-capacity welfare states combine relatively high social protection with moderate defence commitments, reflecting strong revenue bases and institutional capacity. Security-constrained catching-up economies exhibit higher defence effort alongside lower social spending, driven by acute security pressures and more limited fiscal space. A small group of high-income outliers, including Ireland and Luxembourg, combines very high-income levels with unusually low defence commitments. Europe’s defence expansion thus occurred within structurally different fiscal regimes.

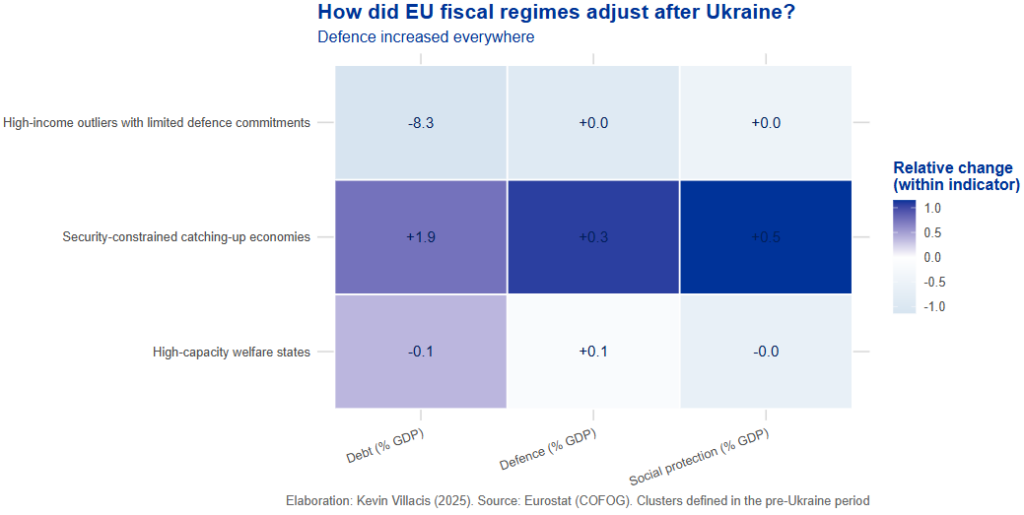

To reinforce this idea, Figure 4 shows how these regimes have adjusted after 2022. Defence spending rose across all groups. High-capacity welfare states absorbed this increase with little erosion of social protection and without major debt accumulation. Catching-up economies relied more on borrowing while modestly expanding social spending. High-income outliers adjusted only marginally. What changed was not Europe’s social model, but the channel and intensity of fiscal adjustment within each regime.

These patterns help explain the growing importance of Union-level initiatives. Instruments such as the Security Action for Europe and the European Defence Industry Programme reflect an emerging understanding of defence as a European public good. By promoting joint procurement and longer-term coordination, these mechanisms can reduce duplication and ease national fiscal pressures.

Europe’s experience since Ukraine shows that security reinforcement does not inevitably undermine social protection. It depends on fiscal credibility, institutional capacity, and Union-level coordination. Defence did not crowd out welfare. Weak fiscal foundations would have.

Kevin Villacis, Highlight 49/2025: Europe’s New Trade-Off: Can Security Reinforcement Coexist with the Social Model?, 15 December 2025, available at www.meig.ch

The views expressed in the MEIG Highlights are personal to the authors and neither reflect the positions of the MEIG Programme nor those of the University of Geneva.