Highlight 47/2025: Italy-Albania migration agreement: human rights implications of offshore asylum processing

Célia de Valensart, 3 December 2025

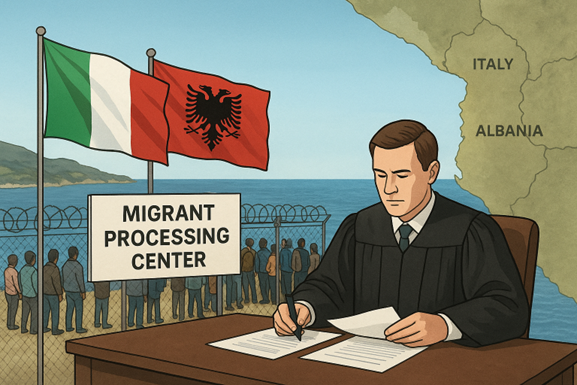

The Italy-Albania Migration Agreement, signed in November 2023, establishes two centres in Albania—Shengjin and Gjader—where migrants intercepted at sea by Italian vessels are transferred for identification, screening, and accelerated asylum or return procedures. Italian administrative and judicial authorities, based in Rome, retain full responsibility for asylum decisions, detention, and appeals, while the centres operate under Italian law and oversight.

This governance arrangement is distinctive: the centres are equated to Italian border zones, and all relevant legal procedures are conducted as if the migrants were physically present in Italy. The de-territorialization of asylum processing is a significant innovation in EU migration governance, blending features of externalisation, border control, and extraterritorial jurisdiction.

The agreement’s governance structure raises critical questions about accountability, transparency, and the equitable sharing of responsibility. While Italy bears the financial and operational costs, Albania retains sovereignty over its territory and jurisdiction in certain areas, such as healthcare and external security. The Albanian Constitutional Court confirmed the agreement’s constitutionality.

However, the governance model faces challenges in ensuring compliance with human rights. The automatic and prolonged detention of migrants, often without individualised assessment, risks breaching international standards on liberty and due process. The physical and legal remoteness of the centres complicates access to legal aid, participation in asylum procedures, and independent monitoring, undermining the right to seek protection.

The centres are managed by Italy, while Albania provides external oversight and security. Migrants’ access to Albanian territory is restricted to the centres and only permitted during administrative procedures. The Italian authorities are responsible for all aspects of the asylum process, including healthcare within the centres, while Albanian authorities retain jurisdiction over external security and healthcare services outside the centres.

The agreement’s implementation has faced judicial scrutiny, with Italian courts repeatedly invalidating detention orders under the agreement, citing insufficient guarantees and unsafe conditions in Albania. The physical and legal remoteness of the centres complicates access to legal aid, participation in asylum procedures, and independent monitoring, undermining the right to seek protection.

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) recently clarified the legal requirements for the designation of safe countries of origin under EU asylum law. In its judgment of 1 August 2025 (Joined Cases C-758/24 and C-759/24), the ECJ ruled that a country can only be designated as safe if it offers adequate protection to its entire population, and not just to certain groups or regions. The Court further held that the information used to justify such a designation must be accessible and verifiable by both applicants and reviewing courts, ensuring effective judicial protection. The ECJ also stated that Member States cannot designate a country as “safe” if the material conditions for safety are not met for all categories of persons. This means that Italy’s attempt to exclude certain categories of persons from the safety assessment is unlawful under current EU law.

In conclusion, the Italy-Albania Agreement exemplifies the evolving governance of migration in Europe, where states increasingly externalise asylum processing to third countries under their own jurisdiction. This model underscores the necessity of robust legal safeguards, transparent oversight, and equitable burden-sharing to uphold human rights and international law.

Célia de Valensart, Highlight 47/2025: Italy-Albania migration agreement: human rights implications of offshore asylum processing, 3 December 2025, available at www.meig.ch

The views expressed in the MEIG Highlights are personal to the authors and neither reflect the positions of the MEIG Programme nor those of the University of Geneva.